Summary

The influences that shaped Eberhard Arnold and led him to a life of radical Christian witness were numerous and diverse: his teenage encounters with poverty and social reform; evangelistic work in the Revival Movement; the earning of a doctoral degree at three prestigious universities; his fellow editors and theologians; the inspired young people of the German Youth Movement; the books he read. At heart, however, his most singular guide was exceptionally simple: the Jesus of the Sermon on the Mount.

Eberhard’s earliest role models included his uncle Ernst Ferdinand Klein, a pastor involved with clerical and social reform, and William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army, both of whom brought him into contact with the Evangelical Revival Movement. In this he took an active part.

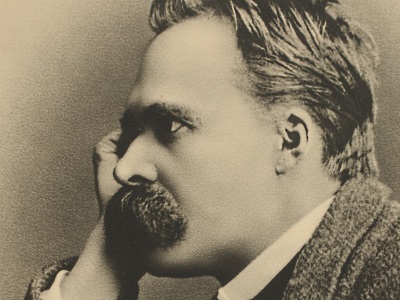

At university he studied education, theology, and finally philosophy, concluding his studies with a doctoral thesis on “Early Christian and Anti-Christian Elements in Friedrich Nietzsche’s Development.” Nietzsche's philosophy continued to play an important role in Eberhard's work throughout his life.

While at university, Eberhard led the local chapter of the Student Christian Movement (SCM). This work brought him in touch with Ludwig von Gerdtell, a former lawyer turned theologian, who fanned the flames of revival with a series of lectures and Bible study classes in people’s homes. Among others, the theologian Karl Heim took part in these meetings, as well as Paul Zander, who later became co-publisher with Eberhard for Die Furche – the magazine of the SCM.

After their marriage in 1909, Eberhard and Emmy hosted frequent gatherings at their home, which were attended by members of Christian youth groups, atheists and anarchists, Quakers, proletarians, and intellectuals. They read and discussed current movements of thought, and authors such as Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, but the discussion frequently returned to the Sermon on the Mount.

Eberhard also took note of the lifestyle of the Free German Youth Movement. These mostly nonreligious young people were intent on creating a new culture outside of bourgeois social norms and artificial urban environments. Eberhard’s encounters with these idealistic youths spurred his own growing recognition that his vision of radical Christianity compelled him to give up his bourgeois existence and search for new, original forms of living.

But along with involvement in such movements, Eberhard remained well acquainted with theological circles. His contemporaries included Rudolf Bultmann and Karl Barth, with whom he corresponded. Additionally he drew on the writings of Johann Christoph Blumhardt and his son Christoph Friedrich. Their radical faith of and emphasis on the power of the Holy Spirit guided Eberhard’s pastoral practice.

The influence of Søren Kierkegaard, the Danish philosopher and theologian, can be seen in Eberhard’s writings. He was also conscious of Mahatma Gandhi’s principles of nonviolence and often referred to him in his talks and correspondence. But it was the social and pacifist ethics of philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Förster that especially helped direct Eberhard in his transformation from militant patriot to committed pacifist.

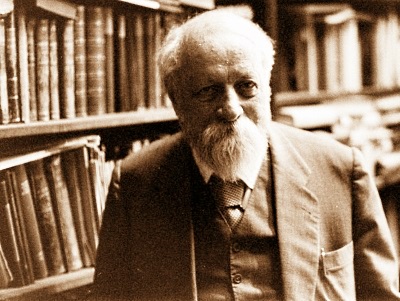

Already in 1910, Eberhard was nudged in the direction of religious socialism by the writings of Zürich pastor, Hermann Kutter. This was later strengthened through his acquaintance and correspondence with theologian and publisher Leonhard Ragaz, also from Switzerland. But it is clear that Eberhard’s plans for community, and many characteristics of the settlement itself, would have been different without the influence of the writer and social philosopher Gustav Landauer.[1]

In guiding the Bruderhof, Eberhard drew on early Anabaptist writers, especially Leonhard Hutter and Michael Sattler. In the years after Eberhard and Emmy started living in Christian community, they became aware that their communal structure was similar to that of the Hutterites, an Anabaptist movement of the sixteenth century that began in the Tyrol under the leadership of Jakob Hutter. Upon learning of the existence of Hutterian communities in North America, Eberhard established a relationship with them.

The rise of National Socialism in the 1930s presented Eberhard and the other members of the Bruderhof with the challenge of remaining faithful in an increasingly hostile state. The nonviolence of the early Anabaptist movement remained a core principle of their identity, despite the persecution they knew it would bring. This also meant that from the start they distanced themselves from the regime.

The Bruderhof’s connections to Jewish communities also strengthened their resolve against the antisemitic aims of the Third Reich. In the 1920s Martin Buber, the Jewish theologian, had stayed at the community as a guest and continued to correspond with Eberhard. In 1930 the Gehringshof estate, an agricultural training center for Jewish emigrants to the newly established kibbutzim in Palestine, was founded near the Bruderhof. Records indicate frequent interaction between the Bruderhof and the Gehringshof and a lively interest in the new Jewish communal movement and Zionism.

Around this time, thanks to an introduction from Lutheran pastor Martin Niemöller, an exchange of ideas occurred between Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Bruderhof. Despite very real intentions on both sides of having Bonhoeffer – who was in England at the time – visit the Bruderhof, these plans never materialized. Still, significant interaction took place between Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Bruderhof via Eberhard’s son Hardy who was then studying in London.

Amid the broader peace movement, the Bruderhof had close ties to the German branch of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation. Eberhard was a long-time friend of the movement’s founder, Friedrich Siegmund-Schultze, and actively participated in its conferences and committees. This connection also helped the Bruderhof establish international ties, which later proved essential to their survival.[2]

1. Markus Baum, Against the Wind (Plough Publishing House 1998), 97.

2. Thomas Nauerth, Zeugnis, Liebe und Widerstand: Der Rhönbruderhof 1933-1937 (Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2018), 26.

Selected Reading

Eberhard Arnold and Nietzsche

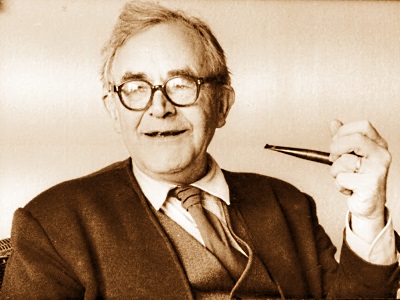

Markus Baum

Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophy, language, and thinking were of great interest to Eberhard Arnold. He completed his doctoral dissertation on Early Christian and Anti-Christian Elements in the Development of Friedrich Nietzsche, and from then on traces of the great impression made on him by this eccentric and extraordinary thinker surfaced in his thought, speech, and action.

Eberhard Arnold and Dietrich Bonhoeffer

While studying in England in 1934, Eberhard Arnold’s son Hardy came in contact with the community of German émigrés living in London, including the German pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer. He found that Bonhoeffer had a keen interest in his experience with communal life at the Bruderhof and in Eberhard Arnold’s writings.

Continue ReadingEberhard Arnold and Judaism

Eberhard Arnold sent his children to visit the local synagogue as part of their religious education and developed in them a deep respect for Judaism and its foundation, the Hebrew Bible / Old Testament. The following offers a brief survey of the Bruderhof's interaction with the Jewish community in their area.

Eberhard Arnold and National Socialism, Part One

Avoiding covert resistance on the one hand and complicity and compromise on the other, Eberhard Arnold guided his community in the face of Nazi threats. They continued to witness to the kingdom of God in Nazi Germany until their expulsion after his death.

Continue Reading